728x90 - Google Ads

728x90 - Google Ads

336x280 - Google Ads

Accuracy of scientifically generated weather forecasts remains limited

336x280 - Google Ads

When the IMD says, for example, that rainfall is expected to be normal this year, it can very well mean that there may be floods in Bihar, eastern UP and West Bengal and severe droughts in Vidarbha or in the western parts of Rajasthan. The average of the two can satisfy the prediction of IMD, although there is disaster everywhere!

300x600 - Google Ads

The India Meteorological Department (IMD) was established in 1875 as a pivotal organisation for weather observation, forecasting and climate monitoring in the Indian subcontinent. Incidentally ‘India’ is the correct word. Many national organisations use ‘Indian’ at the beginning of their names, which I find somewhat racist in its flavour. As someone pointed out, it is the India cricket team that plays against the teams of other countries and not the Indian team!

IMD is the principal government agency for meteorology and related subjects and plays a vital role in disaster management, agriculture, aviation, and public safety by providing critical weather and climate services. Its vision includes achieving high forecast accuracy-zero-error for up to three days and 90 per cent accuracy for a five-day forecast.

As one of the first scientific departments of the Government of India it celebrated its 150th anniversary on January 15, a milestone which is a testament to its long-standing contributions to the field of meteorology and its impact on the nation.

The roots of meteorology in India trace back to ancient times. Early philosophical texts like the Upanishads discuss cloud formation, rain processes, and seasonal cycles, as long back as 3000 BCE. Modern meteorology gained a scientific foundation in the 17th century with the invention of the thermometer, barometer, and the formulation of atmospheric gas laws. The first meteorological observatory in India was established in 1785 at Kolkata.

Having worked in the agriculture and related sectors for over two decades, I enjoyed a close association with IMD. As a member of National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA), in particular, I had the opportunity to study the working of the organisation closely and often visited its headquarters in Lodhi Road, Delhi.

Its distinguished past record and ambitious plans for the future notwithstanding, the fact remains that, at least so far as agriculture is concerned, I found IMD’s forecasts are of limited, if not doubtful, value. Being a scientific organisation, it quite rightly puts out predictions based on studies of weather patterns using various instruments in different types of technology. The forecasts, excellent as they are from a technical point of view, however, are more relevant at the global level and have difficulty in relating to grassroots level requirements. I have for long argued that disaggregated and locally relevant short term forecasts ought to be the objectives which the agency needs to espouse.

Agriculture is a tricky area and what is a good thing for one place can spell disaster for another. Likewise, what is a good event at one time in a given place can, at the wrong time, have extremely adverse consequences-the sauce for the goose not being the same for the gander, in other words.

Take, for example, Anantapur district in Andhra Pradesh, where I began my career in civil service. Groundnut is a common crop there. If it does not rain in the first week of July, it is difficult to plant the seed. Another spell of rainfall is required a few weeks later, to whet the appetite of the growing plant for nourishment. Much later, when it is time for harvesting the crop, a shower, makes it easy for the groundnut to be plucked out of the ground. If any of these events happens at the wrong time, production and productivity will both suffer substantially. When the IMD says, for example, that rainfall is expected to be normal this year, it can very well mean that there may be floods in Bihar, eastern UP and West Bengal and severe droughts in Vidarbha or in the western parts of Rajasthan. The average of the two can satisfy the prediction of IMD, although there is disaster everywhere!

As a member of the NDMA, I found that my earlier feeling, that it is difficult, if not almost impossible, to predict the occurrence of earthquakes had, in fact been scientifically validated. Forecasting, however, is possible in the case of other natural calamities, such as cyclones, floods and droughts.

In the case of cyclones, I was aware that a technology was in vogue in other countries like the USA, by which aircrafts are sent into the eyes of cyclones, to study parameters such as the radius of maximum wind and temperature, which are crucial for anticipating the likely structure and intensity of the storms.

I remember having taken it up with IMD with a view to seeing whether it could be used in India too. It is indeed gratifying that, subsequently, IMD did buy the appropriate technology from the USA. They are waiting to see if the Indian Air Force (IAF) can spare one of the aircrafts available with them, which are known to be suitable for the purpose, could be spared, so that they can also commence the process.

In the meanwhile, it is understood that Taiwan has also started using the method, with the help of the USA.

Despite all the mostly unjustified criticism against them, the weather forecasters, when all is said and done, do a reasonably good job. It is no fault of theirs, after all, that phenomenons such as the butterfly syndrome, make it well-nigh impossible for accurate predictions of the manner in which the climate in the world or the weather in a local situation will behave.

We live in a world which today undoubtedly is free from any gender bias, a world in which women have, quite rightly, and on their own steam, proven their ability to occupy the highest positions in various walks of life, from politics to space travel, and acquitted themselves much better than their male counter parts. William Shakespeare, however, belonged to another era, not quite as enlightened. He would probably have assigned to the entity of weather the feminine gender. In order to correspond with his saying, as Hamlet said, in the play with the same name, ‘Frailty thy name is woman.”

There is, in fact, also a Telugu equivalent expression, reflecting the same spirit, “Kshanakshanikamul javarandra chittamul”, or freely translated, a moment is all that a lady needs to change her mind! A spirit, no doubt, that belonged to a less emancipated times!

There are, after all, limits to even the most scientifically generated weather forecasts. There is this well-known butterfly syndrome in climate, a concept in chaos theory that describes how a small change in the initial conditions can lead to significant and unpredictable outcomes. The fluttering of the wings of a butterfly in Paris, for example, can lead to a super cyclone in the Bay of Bengal!

Talking about weather forecasts reminds me of the time when in the early 1970s, P.V. Narasimha Rao, as Chief Minister of Andhra Pradesh, travelled to Chittoor district to acquaint himself with the devastation caused by a severe drought. And as the Collector of that district at that time, a senior and respected colleague, Valliappan told me later, bursting with laughter, the Prime Minister went around in pouring rain!

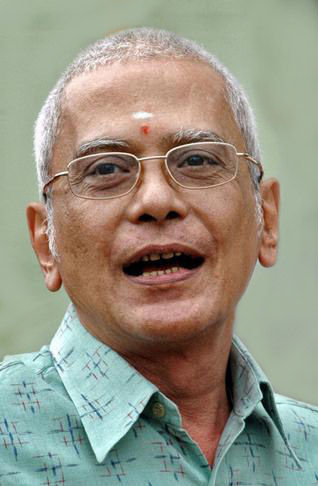

(The writer was formerly Chief Secretary, Government of Andhra Pradesh)